Bell’s Palsy – Diagnosis and Treatment

Inflammatory, Neurological

Context

- Bell’s Palsy is an idiopathic palsy of the facial nerve (cranial nerve VII). It accounts for ~50% of all CN VII palsies1.

- Commonly associated with viral infection, most notably herpes simplex reactivation1.

- CN VII supplies motor innervation to the face, autonomic innervation to salivary and lacrimal glands, and receives sensory innervation from the anterior 2/3 of the tongue as well as part of the external auditory meatus.

- CN VII passes through narrow canals of bone along its course to the face, predisposing it to compression secondary to inflammatory processes, and thus disrupted distal function.

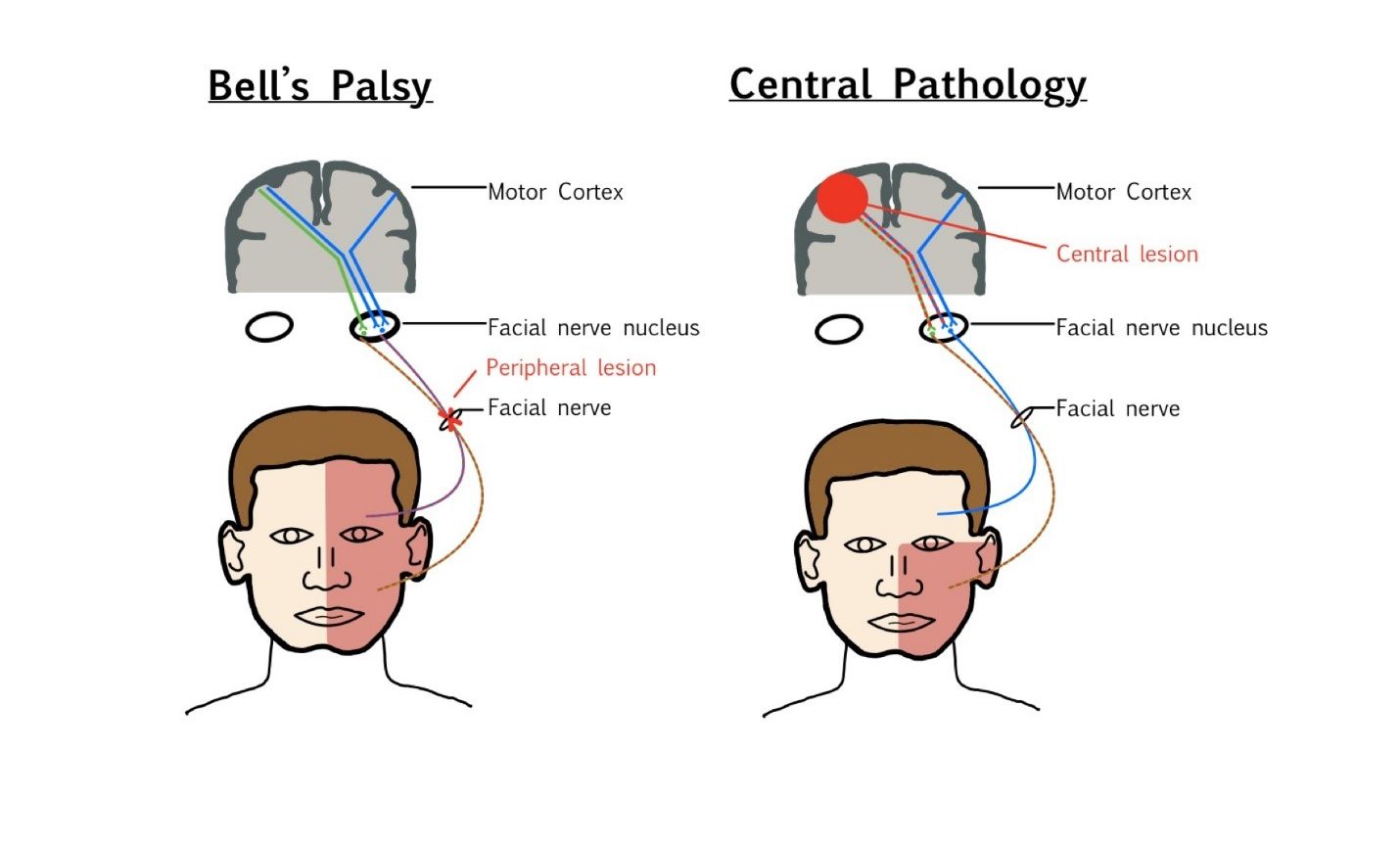

- Unilateral facial motor function is controlled by the contralateral motor cortex through CN VII. The forehead/eyebrow region ALSO receives redundant innervation from the ipsilateral motor cortex. Bell’s palsy is a peripheral CN VII palsy, effecting the entire unilateral face. More sinister central (and often hemispheric) disease spares the forehead because of the redundant innervation.

Diagram by M. Figura

Diagnostic Process

History and Physical

- Bell’s Palsy is primarily a unilateral weakness of the facial muscles. Assess for facial asymmetry and strength. There may also be decreased lacrimal production, dry mouth, hyperacusis and abnormalities of taste.

- 60% of patients may report a viral prodrome2.

- It is CRITICAL to determine if the forehead and eyebrows are affected to the same degree as the rest of the face. Presentations that are forehead sparing raise concern for central pathology including stoke or intracranial mass.

- Onset of symptoms should be abrupt (over the course of 1-3 days). Symptoms that come on insidiously (over weeks – months) or those that present suddenly at their peak should raise concern for an alternative diagnosis.

- Symptoms are progressive for up to 3 weeks, then plateau and begin to improve within 4 months. Cases that fall outside these parameters should raise concern for an alternative diagnosis.

- It is important to perform a thorough neurological exam to ensure that all abnormalities are isolated to cranial nerve VII. Any non-isolated presentations raise concern for an alternative diagnosis.

Investigations

- Bell’s Palsy is a clinical diagnosis, and no further investigation is required in the absence of atypical features2.

- Atypical features indicate a more thorough work up. Neuroimaging should be pursued in the presence of clinical suspicion for stroke, tumor, or other intracranial abnormality.

Diagnostic considerations

- Bell’s Palsy is a clinical diagnosis of exclusion.

- The most serious diagnoses to first rule out are stroke and tumor (intracranial, parotid gland).

- Other diagnoses that could lead to CN VII palsy include trauma, systemic infection (Lyme, mononucleosis), ear infection, Ramsay Hunt syndrome, Guillain Barre syndrome.

- Atypical features that should prompt consideration of alternative diagnosis include systemic symptoms, rash, severe pain, cervical lymphadenopathy, vestibular abnormalities, bilateral involvement, and tick bite in Lyme endemic areas.

Recommended Treatment

Treatment

- Prompt treatment with oral corticosteroids (ideally within 72hrs of symptom onset) is the most is the most efficacious way to optimize recovery and reduce risk of incomplete recovery3.

- Prednisone 60mg PO for 5 days with a 5-day taper is recommended2, although a 7-day course of prednisone (60-80mg/day) is often the most simple regimen used clinically.

- Antivirals are often co-administered clinically due to the common association of herpes simplex. Meta-analysis suggests little to no additional benefit when added to corticosteroid therapy. Antivirals should not be used alone3.

- Eye protection is a key component of therapy as decreased tear production and inability to close the eyelid leaves the cornea predisposed to abrasion, keratitis, and ulceration. Artificial tears should be used during the day along with mechanical protection (eyeglasses, eyepatch) during risky activity. During sleep a more viscous artificial tear preparation should be used along with eye protection. Eye patch should not be applied without gentle taping of the eyelid closed as it is prone to opening under the patch.

Disposition

- Spontaneous recovery by 3-6 months in 70% of cases4, improving to 80-85% when treated appropriately5.

- Follow up with family physician is recommended to monitor progression and resolution of symptoms.

- Discuss returning the ED for onset of atypical neurological symptoms or signs of acute eye complication including trauma, infection, or pain.

Complications

- Incomplete recovery is correlated with the severity of weakness at presentation.

- Late complications include facial spasm and/or contractures in up to 15% of cases4.

- Psychological complications can result from lasting physical symptoms.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Rigorous clinical evidence exists in the treatment of Bell’s Palsy, but there is a lack of clinical evidence indicating causative association to any of the suspected etiologies.

Related Information

Reference List

Schirm J, Mulkens PS. Bell’s palsy and herpes simplex virus. APMIS 1997; 105:815.

Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, Erickson TB, Wilcox SR. Brain and Cranial Nerve Disorders. In: Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2023.

Madhok VB, Gagyor I, Daly F, et al. Corticosteroids for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 7:CD001942.

Peitersen E. The natural history of Bell’s palsy. Am J Otol 1982; 4:107.

Yoo MC, Soh Y, Chon J, et al. Evaluation of Factors Associated With Favorable Outcomes in Adults With Bell Palsy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020; 146:256.

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Feb 08, 2023

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.