Acute Psychosis – Diagnosis

Cardinal Presentations / Presenting Problems, Metabolic / Endocrine, Neurological, Psychiatric and Behaviour, Special Populations, Toxicology

Context

- Psychosis = trouble distinguishing between what is real and what is not, ultimately affecting the way a person thinks, feels, and behaves.

- 3% of people will experience a psychotic episode in their lifetime. The hallmark of these psychoses is schizophrenia which has a worldwide prevalence of 0.5 to 1%.

- Develop acutely or gradually.

- Hallucinations, delusions, disorders of thought, and disorganized speech or behavior.

- Primary (psychiatric/functional) or secondary (medical/organic) etiologies such as substances, medications, toxins, and other medical conditions.

Presentation

- Patients may be agitated, combative, uncooperative, or unable to provide any history.

- Key features of psychotic disorders include one or more of:

- Delusions

- A fixed false belief, out of keeping with the patient’s educational, cultural, and social background, ranging from the clearly implausible to the reasonable and understandable but untrue.

- Common delusions may be grandiose, persecutory, erotomaniac, or referential

- In the ED, a delusion may be difficult to differentiate from a strongly held idea unless it is clearly implausible.

- Hallucinations

- A sensory perception of an external object or event experienced in the absence of a real stimulus.

- Hallucinations – the most common hallucinations are auditory, such as voices originating outside the person.

- Disorganized thinking (speech)

- Common patterns include derailment or loose associations, tangentiality, and word salad.

- Grossly disorganized or abnormal motor behaviour (including catatonia).

- Often manifesting as unpredictable agitation.

- Delusions

- Catatonia is a marked decrease in reactivity to the environment, with features ranging from resistance to instructions (negativism), to maintenance of a rigid or inappropriate posture, to complete absence of motor or verbal response.

- Negative symptoms, including diminished emotional expression, avolition (decreased motivation), alogia (decreased speech), anhedonia (decreased ability to experience pleasure), and asociality (decreased interest in social interaction).

Diagnostic Process

Goals of the ED provider when diagnosing and treating an acutely psychotic patient

- Ensuring safety.

- Emergency treatment and stabilization.

- Identification of comorbid conditions and potential underlying etiology.

- Appropriate disposition.

Ensuring safety of patient, ED staff and other patients

- Create a safe situation to allow further assessment: verbal de-escalation, and/or physical restraints, and/or chemical sedation.

- Patient experiencing psychosis may respond negatively to intensive questioning.

- Patient’s heightened state of anxiety has contributed to their current psychotic state, and as such:

- Psychotic patients will remember aspects of the encounter which may affect future interactions.

- Foster an environment where trust can be established, and consider recruiting trusted others (family, friends, case managers).

- Avoid challenging or questioning the validity of delusional themes, explain empathically that there are reasons they are experiencing things differently.

- Allow the patient an opportunity to express their concerns, and identify unmet needs that can be easily corrected (e.g. inadequate pain control, communication failures, social concerns).

- For the patient who is mute or otherwise difficult to engage in an interview, speaking about neutral subjects, such as the weather or sports, may help alleviate anxiety and open up the patient to answering some basic questions.

Emergency treatment and stabilization

-

-

- Most likely, the patient feels that they have been violated in some way — either due to intrusive voices, paranoia, somatic delusions, or some other terrifying symptom. The ED physician and mental health professional should maximize the patient’s sense of autonomy and self-determination while avoiding coercion to the greatest degree possible, ( i.e. allowing the patient to choose the route of administration).

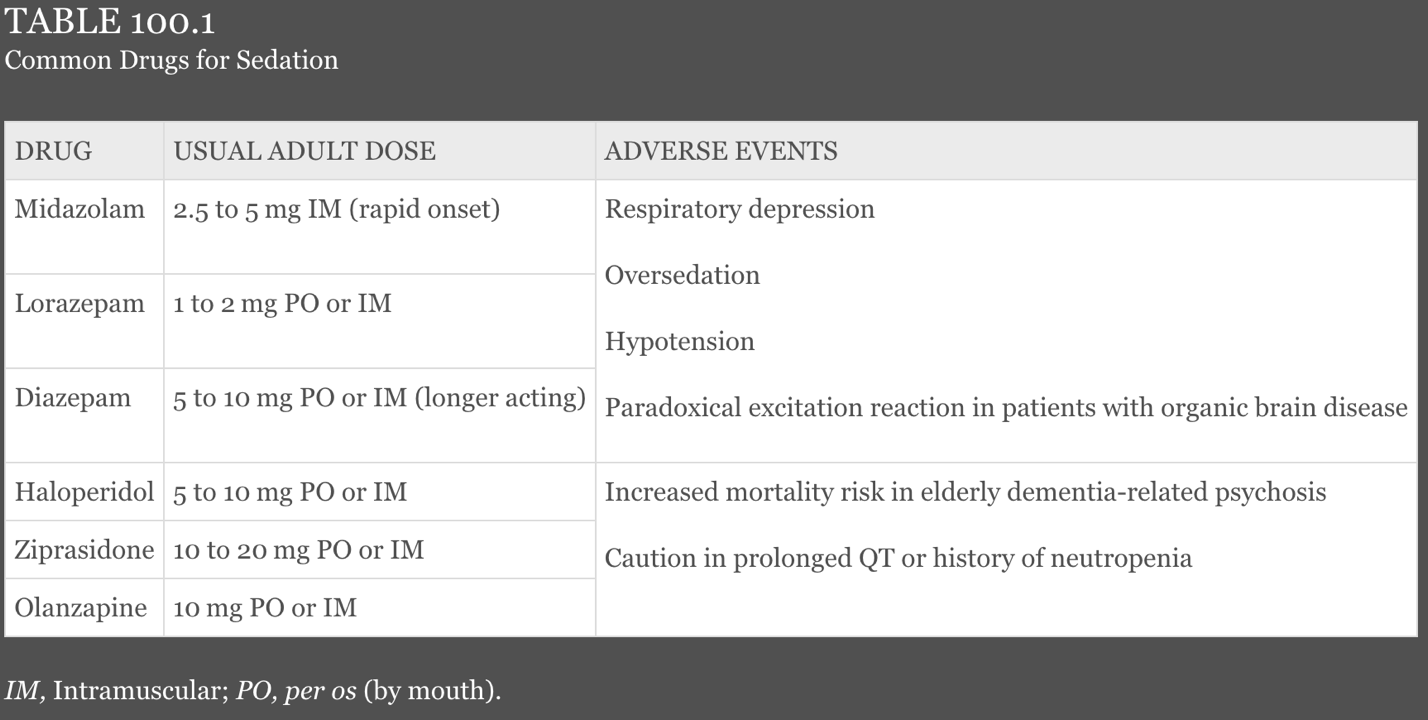

- Pharmacotherapy

-

When choosing route of administration, consider speed of onset and reliability of delivery.

- Administered orally for receptive patients, or via IM/IV for those who are agitated.

- Benzodiazepines and antipsychotics are the two medications most commonly used.

- Using a single agent or, for more disturbed patients, a combination of the two classes, can be considered.

- Combined with concurrent physical restraint and the risk of previously ingested intoxicants, there is significant risk for over-sedation and respiratory compromise.

- The combination of haloperidol and lorazepam causes respiratory depression in up to 50% of patients with a significant number also experiencing a hypoxic event. Fortunately, most episodes are quickly corrected with verbal stimulation or airway repositioning.

- Recommend monitoring in chemically restrained patients to detect early signs of respiratory depression.

- Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications are common and can mimic psychosis

- Most commonly associated with typical antipsychotics.

- Acute dystonia

- More common in younger patients and those who have never taken antipsychotic drugs before.

- Often recur despite reduction in or discontinuation of offending antipsychotic.

- Muscle spasms of neck, face, and back are most common forms, but oculogyric crisis and laryngospasm can occur.

- Treat with:

- Benztropine, 1-2mg IV or IM, or

- Diphenhydramine, 25-50mg IV

- For persistent dystonias, both medications may be used, and benzodiazepines may be added or used prophylactically.

- Akathisia (motor restlessness)

- A sensation of motor restlessness with a subjective desire to move.

- Can begin several days to weeks after initiation of antipsychotic treatment.

- Management can be difficult

- If possible, and with consultation, consider decreasing the dose of the antipsychotic.

- Benzodiazepines or beta-blockers are probably best.

Identification of comorbid conditions and potential underlying etiology

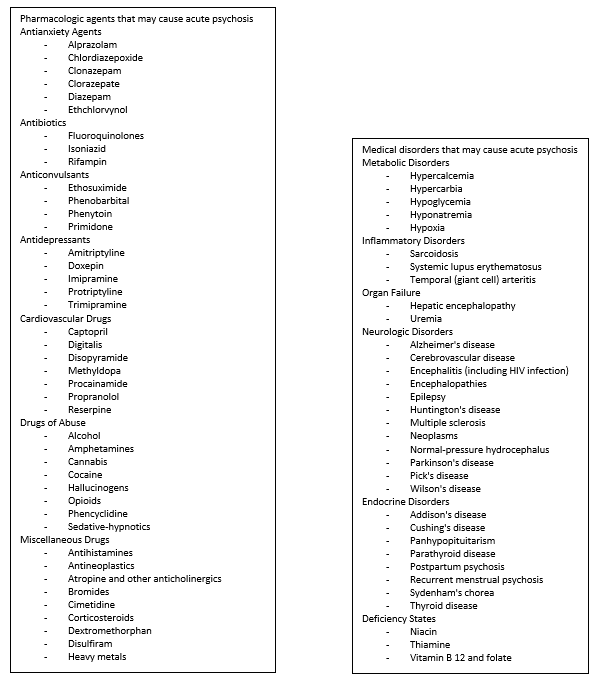

- Numerous acute and chronic medical conditions can precipitate psychosis.

- Additionally, patients with underlying psychiatric disease may develop medical disorders that can exacerbate behavioural symptoms.

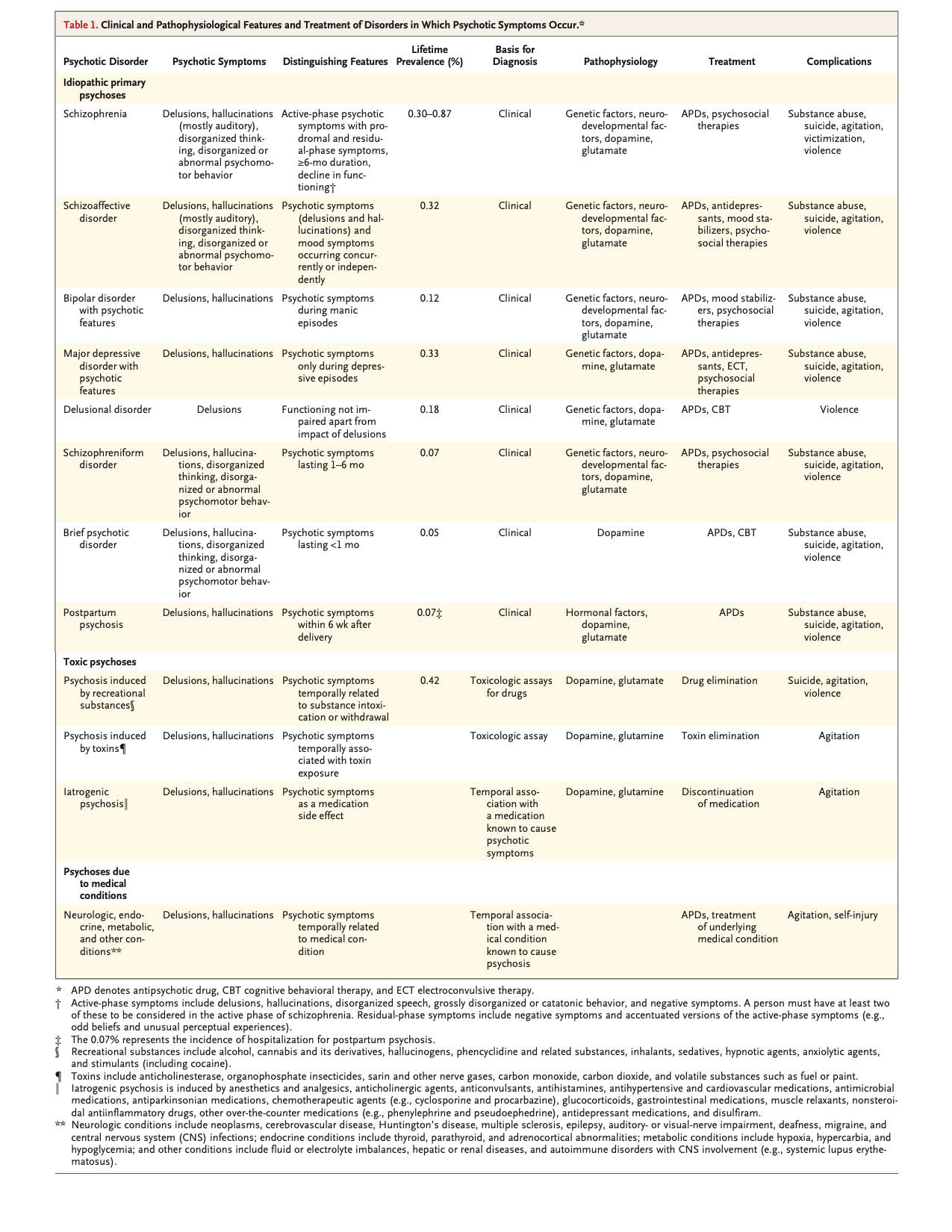

- While the DSM lists many types of psychotic disorders with individual criteria, in the ED it is typically not required or relevant to distinguish between these specific psychiatric diagnoses.

- Assess for and rule out medical causes before attributing psychosis to primary psychiatric illness.

- Infections (encephalitis, meningitis, sepsis)

- CNS conditions (stroke, seizure, Parkinson’s disease, brain tumor)

- Metabolic derangements (hypoglycemia, hepatic encephalopathy)

- Some features that can help differentiate primary psychiatric causes are prominent auditory hallucinations, family history of psychosis, and insidious onset in late teens to mid-twenties.

- Medical delirium is common in older patients and often mistaken for dementia, psychosis, or depression.

- Important differentiating features:

- A new onset of symptoms

- Acute change in mental status

- Recent fluctuation in behavioural symptoms

- Onset > 50

- Onset of symptoms after patient has already been admitted

- Presence of non-auditory hallucinations

- Presence of lethargy, abnormal vital signs, poor performance on cognitive testing (especially orientation to time, place, person)

- Many patients have been previously diagnosed with a psychiatric condition.

- If this is the case, identify if the current presentation represents an acute change from baseline and/or if the current presentation may be confounded by another condition requiring treatment.

- Newly symptomatic patients warrant more extensive medical evaluation than those with previously diagnosed psychotic disorders.

- Determine if presentation is result of medical condition, medication, substance, or a true new onset of primary psychiatric illness.

- On physical examination:

- No specific physical findings associated with psychotic disorders.

- The goal of the physical exam in this setting is to exclude other potential causes of psychotic symptoms.

- Vigilance is required for injuries, whether environmental, self-inflicted, or a result of combative behaviour or restraints.

- On imaging:

- Routine neuroimaging in the evaluation of psychosis is controversial.

- Neuroimaging may exclude rare and treatable causes of psychosis and should be considered on an individual basis.

- On laboratory investigations:

- Urine toxicology rarely affects ED management and need not be routinely performed.

- Extensive laboratory testing for otherwise stable, cooperative, and previously diagnosed psychiatric patients is of low yield in most cases.

Appropriate disposition

- The decision for inpatient psychiatric admission is not always precise, and should be guided by etiology of the psychosis, response to treatment, consideration of patient and community safety, and appropriate outpatient follow-up plans.

- Patients thought to be violent, at risk of self-harm, or unable to care for themselves typically require emergent psychiatric evaluation and possibly inpatient psychiatric care.

- Patients with new onset primary psychosis or those with worsening of underlying psychotic symptoms should have psychiatric consultation in the ED and likely be admitted.

- Patients with known psychoses under apparent good control should be referred for outpatient management, ideally in consultation with patient’s psychiatric treatment provider.

- Patients with psychosis secondary to medical condition or those with comorbidities should be managed accordingly.

- Can they manage treatment and follow-up as an outpatient, or would they benefit from hospitalization?

- In many cases of schizophrenia, psychotic symptoms are ongoing, sometimes despite good pharmacological and psychotherapeutic management.

- The mere presence of psychotic symptoms in a patient who experiences such symptoms at baseline does not in itself warrant inpatient psychiatric hospitalization.

- Recruiting family or friends familiar with the patient can help establish that the patient is back to their baseline state.

- In all cases, a safe transition to the community setting requires adequate social support, including follow-up with a mental health service.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Knowledge of psychotic disorders is limited, especially with respect to cause and pathological basis. As such, diagnostic tests are neither sensitive nor specific enough to reliably diagnose individual cases of psychosis, and pharmacological treatments are not consistently useful for psychotic symptoms of all etiologies.

Related Information

Reference List

Addington D, Abidi S, Garcia-Ortega I, Honer WG, Ismail Z. Canadian guidelines for the assessment and diagnosis of patients with schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(9):594-603.

Bromley S, Choi MA, Faruqui S. First Episode Psychosis: An Information Guide. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2015.

Byrne P. Managing the acute psychotic episode. BMJ. 2007;334(7595):686-692.

Furiato AJ, Ruffalo ML. Schizophrenia in the emergency department: psychologically and psychodynamically informed practices. Psychiatric Times. Published online November 11, 2021.

Griswold KS, Del Regno PA, Berger RC. Recognition and Differential Diagnosis of Psychosis in Primary Care. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91(12):856-863.

Kelly MP, Shapshak D. Chapter 100: Thought Disorders. In: Walls RM, Hockberger RS, Gausche-Hill M, eds. Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice. Ninth edition. Elsevier; 2017:1341-1345.

Lieberman JA, First MB. Psychotic disorders. Ropper AH, ed. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(3):270-280.

Sami MB, Shiers D, Latif S, Bhattacharyya S. Early psychosis for the non-specialist doctor. BMJ. Published online November 8, 2017:j4578.

Tobias AZ. Chapter 290: Psychoses. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. McGraw-Hill Education; 2020:1952-1956.

Related Information

OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Jun 11, 2022

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.