Acute Dyspnea – Diagnosis Summary

Respiratory

Context

Dyspnea or shortness of breath is a common chief complaint among emergency department patients.

Assessment varies based on the severity of the dyspnea and need for intervention.

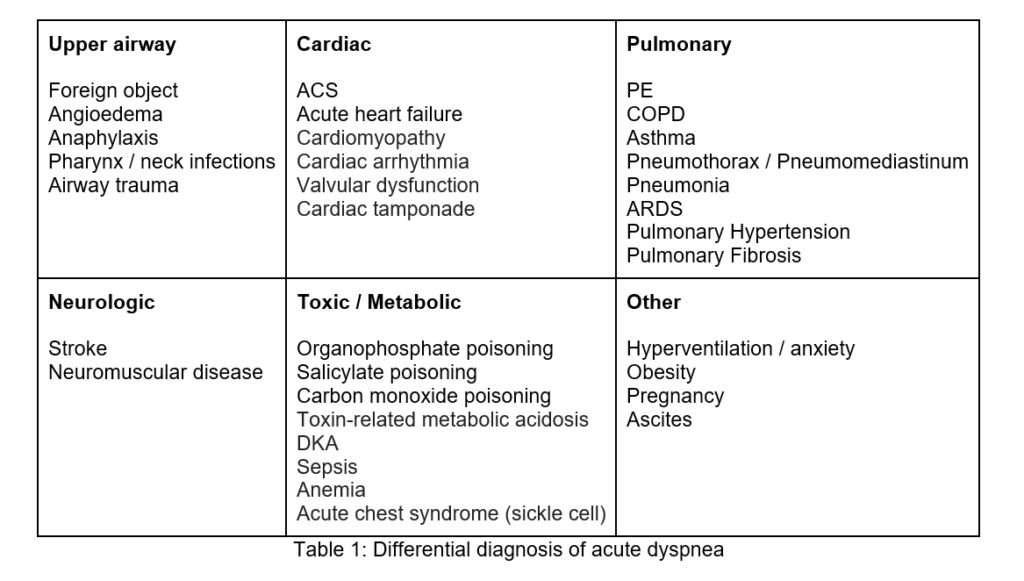

Differential diagnosis

There are many (some life-threatening) causes of acute dyspnea and they can be organized by system as follows (Table 1):

Establish severity of airway patency and ventilation status and manage accordingly.1

- Mental status: Decreased LOC, agitation, or altered mental status.

- Respiratory status:

- Cyanosis.

- Tiring – Inability to maintain respiratory effort, slow RR is a terminal event.

- Inability to speak in full sentences.

- Increased work of breathing: accessory muscle use, profound diaphoresis.

- Audible stridor, wheezing from obstruction or bronchospasm.

- Sitting in tripod position, unable to lie supine.

- Signs of an allergic reaction.

- Vital signs:

- Pulse oximetry:

- inaccurate in cases of hypothermia, shock, carbon monoxide poisoning, and methemoglobinemia.

- SpO2 should be >95% for healthy individuals.

- 92-95% for patients who are older, smoke or are obese.

- can be <92% for patients with severe chronic lung disease.

- BP – Hypotension may indicate sepsis / shock picture.

- HR – tachyarrhythmias rarely can lead to dyspnea and tachycardia can be a finding in PE but are more commonly tachycardia is secondary to the cause of the dyspnea.

- Pulse oximetry:

Once stabilized/if stable: Determine etiology to guide management

Acute dyspnea (over minutes to hours) has a relatively limited number of causes, including:

- ACS.

- HF.

- Cardiac tamponade.

- Bronchospasm.

- PE.

- Pneumothorax.

- Infection.

- Massive pleural effusion – blood or effusion.

- Upper airway obstruction.

- ARDS.

Past medical history often leads to most likely diagnosis but beware of two conditions: ie. PE or pneumonia in COPD or PTX in asthma exacerbations.

Historical features can help:

- Chest pain – ACS, PE, pneumothorax etc.

- Fever – pneumonia, aspirin poisoning, etc.

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) – HF, COPD (asthma or GERD).

- Hemoptysis – severe valvular disease (e.g., mitral stenosis), PE, tuberculosis, malignancy.

- Cough / sputum – white or pink frothy sputum (HF), purulent sputum (pneumonia), nonproductive cough (asthma, heart failure, respiratory infection, or PE).

- Trauma – pneumothorax, hemothorax, cardiac tamponade.

- Wheezing – bronchospasm, foreign body, pulmonary edema.

Physical examination includes an appropriate examination of respiratory, cardiovascular, skin, and extremities.2

Investigations

CXR and ECG should be obtained in most patients who present to ED with acute dyspnea.

CXR: can help in the diagnosis of:

- Acute HF – Ultrasound is more sensitive than CXR.3

- Pneumonia.

- Pneumothorax.

- COPD / asthma complication such as pneumothorax or pneumonia.

ECG: can help in the diagnosis of:

- cardiac ischemia.

- PE.

- pericardial effusion.

- old ECG helpful for comparison.

Ultrasound: Immediate use of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) in combination with standard work-up of dyspneic patients in ED can help improve the accuracy of diagnosis.4 Combined heart, lung, and IVC ultrasound has overall high specificity and lower sensitivities for etiologies of acute dyspnea in the emergency department and has a good correlation with diagnosis determined by the emergency physician.5

- Lung views: help with diagnosis of:

- Pneumothorax.

- Pulmonary edema.

- Pleural effusions.

- Pneumonia.

- Cardiac views: to assess right heart strain, global cardiac dysfunction, focal wall motion abnormalities, and help diagnose pericardial effusion. Overall, echocardiography has a low sensitivity for diagnosing PE. Accuracy is higher in diagnosis of massive PE. Regional wall motion abnormalities sparing the RV apex (McConnell’s sign) are particularly suggestive of PE.6

- IVC views: collapsible IVC helps rule out obstructive shock (PE, pericardial effusion, tension pneumothorax).

Lab

- Cardiac biomarkers

- serial troponin to help rule out ACS.

- not specific to ACS, can be elevated in PE, sepsis, pericarditis, myocarditis, etc.

- BNP

- Limited role but if elevated, can help diagnose HF.

- Non-specific – can be elevated in renal failure, ACS, PE, etc.

- D-dimer

- To rule out PE in patients with a low probability of PE (Wells score 0-1).

- Non-specific – can be elevated in malignancy, recent surgery, pregnancy, etc.

- Blood gas

- Venous BG and serum bicarbonate – to determine the acid-base status of the patient or need for more aggressive management.

- Methemoglobin and CO levels can also be added.

- Consider ASA overdose

Other investigations

- CT chest / VQ scan

- CT chest can help diagnose

- Malignancy.

- Pneumonia.

- PE (patients with moderate to high probability of PE, who are not suitable for d-dimer, should receive a CTPE).

- Ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scanning – alternative method for diagnosing PE in patients unsuitable for CTPE.

- CT chest can help diagnose

- Peak expiratory flow (PEF) rate

- to help distinguish pulmonary and cardiac causes of dyspnea.

- to determine severity of bronchoconstriction severe asthma.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Moderate – Evidence comes from a wide range of studies addressing the etiology and diagnosis of acute dyspnea, that are in relative agreement with each other.

Related Information

Reference List

Retractions www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003322.htm (Accessed on February 02, 2006).

Wipf JE, Lipsky BA, Hirschmann JV, et al. Diagnosing pneumonia by physical examination: relevant or relic? Arch Intern Med 1999; 159:1082.

Collins SP, Lindsell CJ, Storrow AB, et al. Prevalence of negative chest radiography results in the emergency department patient with decompensated heart failure. Ann Emerg Med 2006; 47:13.

Pirozzi, Concetta, et al. “Immediate versus delayed integrated point-of-care-ultrasonography to manage acute dyspnea in the emergency department.” Critical ultrasound journal 6.1 (2014): 1-8.

Zanobetti M, Scorpiniti M, Gigli C, Nazerian P, Vanni S, Innocenti F, et al. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography for Evaluation of Acute Dyspnea in the ED. Chest. 2017 Jun;151(6):1295-1301. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.02.003. Epub 2017 Feb 16. PMID: 28212836.

Sosland, Rachel P., and Kamal Gupta. “McConnell’s Sign.” Circulation 118.15 (2008): e517-e518.

Related Information

OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Dec 17, 2021

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.