Oral Rehydration For Adults – Treatment

Critical Care / Resuscitation, Gastrointestinal, Infections, Pediatrics

Context

- This summary is specific for adults (age >17 years). For children please see Gastroenteritis in Children: https://trekk.ca/system/assets/assets/attachments/357/original/2019-03-21_BLR_Gastroenteritis_v_3.0.pdf?1553261651

- Suitable for dehydration causes primarily being diarrhea but vomiting not an absolute contraindication to trial of antiemetic and Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS)

- Adults who are at higher risk of complication from dehydration include:

- People aged 65 years and over, in particular nursing home or limited mobility

- Pregnant women

- People with a chronic disease such as diabetes

- Excludes (most) patients with:

- Diabetic emergency

- Acute renal failure/dialysis dependent

- Sepsis

- Hypotension

- Shock (eg from blood loss)

- Heart failure

- Potential intrabdominal catastrophe (obstruction, ischemia, appendicitis)

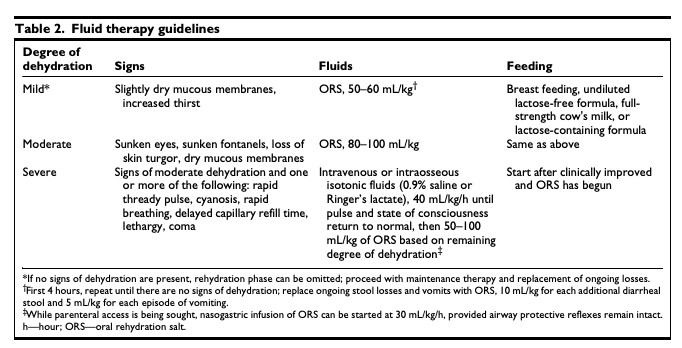

- Severe dehydration (see image below)

- ORS has been shown to reduced mortality and other dehydration related illness/complications:

- reduced serum osmolality to normal levels for independent, community-dwelling, elderly individuals with pre-dehydration (Ushigome et al., 2016).

- Intravenous (IV) rehydration is more invasive, requires more resources, may not produce better outcomes and may not always be readily available.

- After exercise-induced dehydration, IV and oral were equally effective as rehydration treatments (Castellani et al., 1997).

(Sentongo, 2004)

(Patino et al., 2018)

Oral rehydration therapy/treatment (ORT) has been shown to be as effective as IV fluids in moderately dehydrated children in ED (Spandorfer, 2005)

7. Optimal formulation of ORS not standardized:

- WHOand UNICEF jointly have developed official guidelines for the manufacture of oral rehydration solution:

- includes sodium chloride, sodium citrate, potassium chloride, and glucose.[1]

- Glucose facilitates the absorption of sodium (and water) in a 1:1 ratio in small intestine. (WHO)

- Sodium and potassium are needed to replace losses during diarrhoea and vomiting; adding citrate to the formula corrects acidosis that can occur from diarrhoea and dehydration.

- Oral rehydration therapy can be complicated by emesis:

Recommend trial of metoclopramide (Maxeran) (10 mg IM), prochlorperazine (Stemetil) (12.5 IM), or ondansetron (Zofran), 4-8 mg po q8h prn. Metoclopramide in pregnancy.

Recommended Treatment

- Assess level of dehydration (see figure POAC)

- Investigations may not be needed:

- Stool culture

- Urine dip/culture

- Glucose

- Electrolytes

- Pregnancy test

- WHO recommends: osmolarity ORS containing 75 mEq/l sodium, 75 mmol/l glucose (for a total osmolarity of 245 mOsm/l)

- If recent or active vomiting, antiemetic (e.g. Ondansetron) should be given prior to ORS (Hendrikson et al., 2018)

Approach to rehydration: (CDC)

NOTE: This guideline is specific to Cholera so may not apply in many other causes of gastroenteritis. THERE IS A WIDE VARIATION IN RECOMMENDED VOLUMES/TIME. Each clinical situation is unique – your clinical judgment supersedes these recommendations.

NOTE: This guideline is specific to Cholera so may not apply in many other causes of gastroenteritis. THERE IS A WIDE VARIATION IN RECOMMENDED VOLUMES/TIME. Each clinical situation is unique – your clinical judgement supersedes these recommendations.

- Administer ORS immediately to dehydrated patients who can sit up and drink independently. (if ORS not available, provide broth or water, avoiding sugary or sports drinks that can worsen diarrhea)

- Offer small amounts frequently.

- In older children and adults 100mls of ORS q 5 minutes is the goal in severe diseases as in Cholera.

- A rough guide = patient weight (kg) x 75 = mLs/4hrs. Applicable to pediatric patients as well. Give more if needed.

- NOTE: Using the above formula a 70 kg person would need 5 litres over 4 hours or 1.3 L per hour = a lot in someone not feeling well and/or has significant co-morbid disease. Another simpler way to look at this is that during initial rehydration, patients can consume up to 1 L/hr (or 20mL/kg in pediatric patients).

- Attempt to match Ins/Outs.

- If patient is vomiting, can administer via NG tube – however usually start IV if available.

- Reassess every hour. If severe dehydration is suspected, re-assess every 15-30 minutes and consider IV rehydration sooner rather than later.

Eg: Hydralyte: 200mL q 30 minutes (if using liquid). Risk of overhydration is not a concern. (Woodward, 2013)

Other guidelines indicate goal is 3-4L oral fluids over 24 hours which may reflect less severe disease (equals 150 mls /hour). (POAC clinical guideline).

Criteria For Hospital Admission

Failed oral and IV rehydration; Unable to take oral fluids; Unstable hemodynamics; Significant lab abnormalities

Criteria For Safe Discharge Home

Two examples of commercially available rehydration fluids include:

- Gastrolyte Oral Rehydration Salts – Fruit Flavoured – 10 x 4.9g (London Drugs)

- Electrolyte Gastro Oral Rehydration Solution Instant Mix Powder Sachets Orange 8X 4.93g (Shoppers Drug Mart)

Home made ORS recipe:

- Half (1/2) level teaspoon of Salt

- Six (6) level teaspoons of Sugar

- One (1) Litre of clean drinking or boiled water and then cooled 5 cupfuls (each cup about 200 ml.)

- Source: rehydrate.org

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

High, multiple studies have shown minimal harm and improved outcomes. WHO has also studied extensively and has shown improvement in patient condition.

Related Information

Reference List

Patiño, A. M., Marsh, R. H., Nilles, E. J., Baugh, C. W., Rouhani, S. A., & Kayden, S. (2018). Facing the shortage of IV fluids — A hospital-based oral rehydration strategy. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(16), 1475-1477. doi:10.1056/nejmp1801772

Hendrickson, M. A., Zaremba, J., Wey, A. R., Gaillard, P. R., & Kharbanda, A. B. (2018). The use of a triage-based protocol for oral rehydration in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatric Emergency Care, 34(4), 227-232. doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000001070

Castellani, J. W., Maresh, C. M., Armstrong, L. E., Kenefick, R. W., Riebe, D., Echegaray, M., . . . Castracane, V. D. (1997). Intravenous vs. oral rehydration: Effects on subsequent exercise-heat stress. Journal of Applied Physiology, 82(3), 799-806. doi:10.1152/jappl.1997.82.3.799

Spandorfer, P. R. (2005). Oral versus intravenous rehydration of moderately dehydrated children: A randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics (Evanston), 115(2), 295-301. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-0245

Ushigome, K., Taniguchi, H., & Ichimura, M. (2016). MON-P018: The usefulness of oral rehydration therapy in pre-dehydration: An interventional study on independent, community-dwelling, elderly individuals. Clinical Nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland), 35, S160-S160. doi:10.1016/S0261-5614(16)30652-5

Sentongo, T. A. (2004). The use of oral rehydration solutions in children and adults. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 6(4), 307-313. doi:10.1007/s11894-004-0083-5)

POAC Clinical Guideline: Acute Adult Dehydration (2015). https://www.poac.co.nz/site_files/359/upload_files/AdultDehydrationGuidelineFinal2015(1)(1).pdf?dl=1

Rehydration Therapy. (2020, October 02). Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/treatment/rehydration-therapy.html

Woodward, M. (2013). Guidelines to effective Hydration in Aged Care Facilities. https://www.mcgill.ca/familymed/files/familymed/effective_hydration_in_elderly.pdf

- Source: Sentongo, T. A. (2004).

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Jan 01, 2020

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.