Postpartum Hemorrhage: Diagnosis and Management

Obstetrics and Gynecology

Context

- Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the world’s top five causes of maternal morbidity and mortality.

- PPH is the leading cause of maternal death in low-income countries.

- Affects approximately 3 – 5% of obstetric patients globally.

- Causes approximately 25% of maternal deaths worldwide.

- Due to changes in obstetrical practice in recent years (increasing rates of caesarean section (CS), advanced maternal age and a larger proportion of multiple gestations) incidence of PPH has been increasing in Canada, the United States and Australia over the past decade.

- The most common form of obstetrical hemorrhage is primary postpartum hemorrhage, which occurs within 24 hours after giving birth.

- Timely recognition and appropriate management of PPH is critical to prevent maternal deaths.

Diagnostic Process

Defining Primary, Secondary and Severe PPH

- World Health Organization: Maternal blood loss ≥ 500 mL for a vaginal birth or ≥ 1000 mL for a CS.

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: cumulative blood loss ≥ 1000 mL or any loss that results in signs or symptoms of hypovolemia or haemodynamic instability within 24 hours of birth.

- Severe PPH: blood loss > 1500 mL for either a vaginal birth or CS and may lead to signs and symptoms such as orthostasis, hypotension, tachycardia, nausea, dyspnea, oliguria and chest pain.

- Primary PPH occurs < 24 hours after delivery while secondary PPH occurs >24 hours after birth until 12 weeks postpartum.

Diagnosis of Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Recognition of excessive bleeding and physical examination to determine its cause.

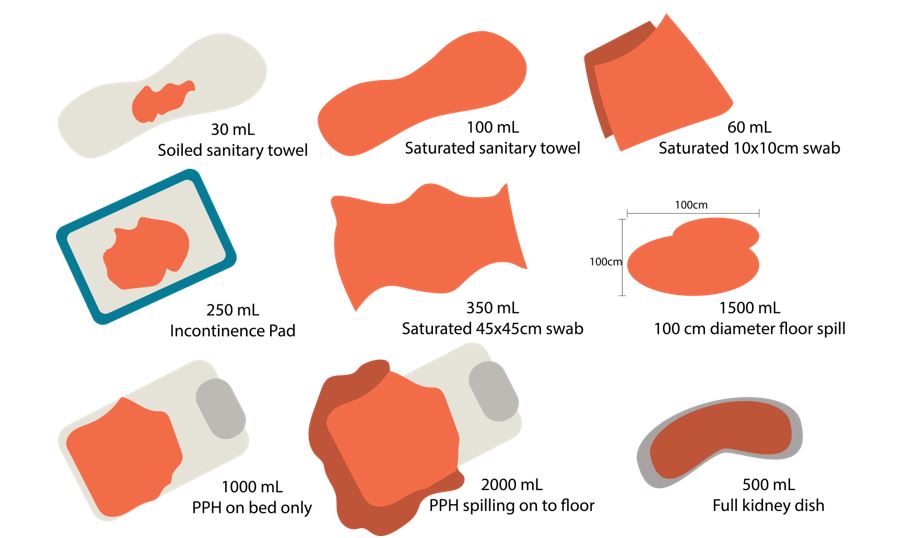

- Care providers inaccurate at visual estimation of blood losses.

- Quantitative measurement should involve a systematic approach such as weighing blood collected in a drape or bedpan placed under the buttocks, by weighing blood-soaked pads, sponges and clots.

- Limitation is the potential for measurement of non-blood fluids: amniotic and urine.

Causes of PPH

- The four T’s mnemonic:

- Tone – urinary atony (80%)

- Trauma – laceration, hematoma, inversion or rupture (20%)

- Tissue – retained tissue or overly-invasive placenta (10%)

- Coagulopathy – inherited disorder of coagulation (1%)

- 80% of PPH is due to uterine atony (i.e. lack of contraction). May be associated with retained tissue, placental disorders, and uterine abnormalities.

- Trauma-related bleeding can result from lacerations or uterine rupture as a result of natural delivery or obstetrical interventions. During CS, hemorrhage can occur due to spontaneous tearing of the uterine incision or delivery of the fetus through the incision.

- Retained products of conception such as placental fragments or blood clots, as well as an overly invasive, or adherent placenta are another common cause of PPH because they inhibit effective uterine contraction.

- Coagulation defects should be considered in cases where the patient does not respond to oxytocin or uterine massage, and/or when the patient’s blood does not clot in the bedside receptacles within 5-10 minutes of delivery.

Management

Prevention and Management

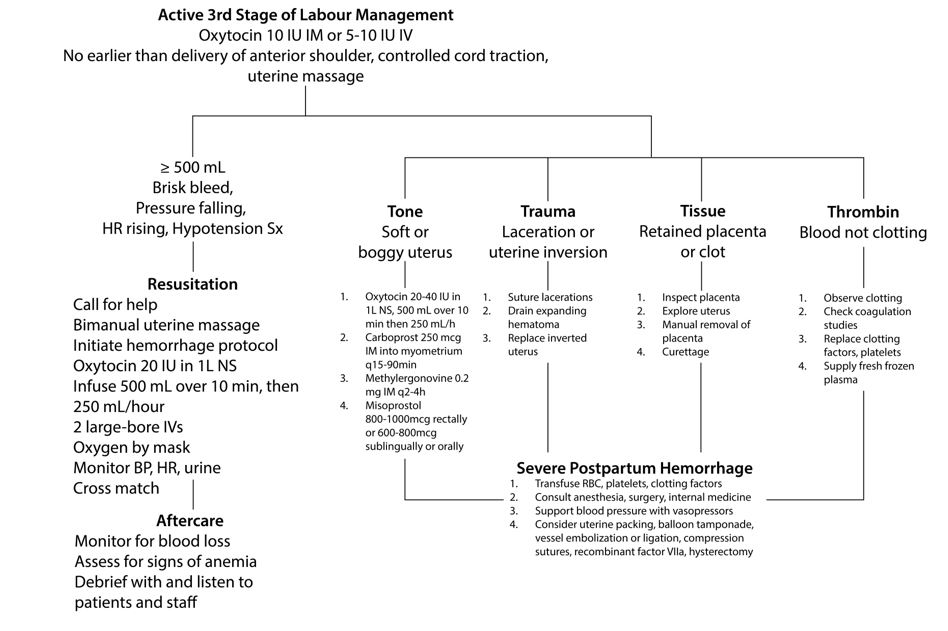

Diagnostic algorithm and decision aid for management.

- Treatment is determined by the cause as illustrated in the above algorithm and requires several interventions simultaneously. Thus, it is important to have a sufficient number of skilled care providers to support the resuscitation attempt.

- Call for help from on-call obstetrician, nurses, anesthesiologist etc.

- Ensure continuous monitoring of vital signs and quantification of blood loss.

- Perform bimanual uterine massage and deliver 20 IU of oxytocin in 1 L normal saline; infuse the first 500 mL over ten minutes and then 250 mL every hour following. Massage should be maintained while other interventions are being initiated and should continue until the uterus contracts firmly and bleeding subsides.

- Lab work including complete blood count, type and crossmatch.

- Establish adequate IV access at two separate sites with large-bore needles (14-16 gauge).

- Resuscitate patient with crystalloid solution and blood (target systolic blood pressure at 90 mmHg and urine output at >30 mL/hour).

- Operating room as soon as is practical for definitive management.

- Provide adequate anesthesia.

- Perform vaginal, abdominal and rectal examinations, looking for lacerations and abdominal or vulvar hematomas. Rapidly assess uterine tone, assess for uterine inversion and examine the uterine cavity for signs of rupture or retained products of conception. Often this is done in OR.

- Administer tranexamic acid at a rate of 1-gram over 10-20 minutes (infusion > 1mL/minute can cause hypotension). If bleeding persists after 30 minutes, administer a second 1-gram dose.

- If uterine rupture is the cause hysterectomy is often required.

- If uterine atony is determined to be the cause of hemorrhage and is not controlled by oxytocin and uterine massage alone, prompt administration of carboprost tromethamine and/or methylergonovine is recommended – done by OBSGYNE.

- If pharmacological interventions are ineffective at promoting increased uterine tone and stopping the hemorrhage, a tamponade balloon or vacuum-induced suction device should be placed and uterotonic drugs should be continued until bleeding subsides.

- If a clotting disorder is suspected, check coagulation studies, replace clotting factors and platelets, and provide fresh frozen plasma.

- If hemorrhage is severe, transfuse red blood cells, platelets and/or clotting factors (Massive Transfusion Protocol) and support the blood pressure with vasopressors; consider uterine packing, balloon tamponade, ligations, factor VIIa, or hysterectomy.

Pharmacological Interventions for Treating Uterine Atony

- Oxytocin is initiated immediately after delivery of the infant at a rate of 40 units in 1 L of normal saline IV or 10 units IM.

- If bleeding persists after administration of oxytocin, carboprost tromethamine and/or methylergonovine should be initiated (OBSGYNE). Generally, 250 mcg of carboprost tromethamine is injected directly into the myometrium either vaginally or transabdominal every 15-90 minutes. A total of eight doses of carboprost tromethamine may be given at least 15 minutes apart. 0.2 mg of methylergonovine may be given directly into the myometrium (never IV) every 2-4 hours as needed.

- Sublingual misoprostol is useful for reducing blood loss in cases where carboprost tromethamine or methylergonovine are unavailable or contraindicated (peak concentration achieved within 30 minutes).

- Dinoprostone (20 mg vaginal or rectal suppository) is an alternative to misoprostol.

- Carbetocin is a long-acting analog of oxytocin, which is given as a single slow intravenous injection (over one minute) and appears to be as effective as oxytocin.

Procedural Interventions

- Uterine tamponade

- Intrauterine balloon catheter.

- Intrauterine pack.

- Vacuum-induced uterine tamponade.

Quality Of Evidence?

High

We are highly confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. There is a wide range of studies included in the analyses with no major limitations, there is little variation between studies, and the summary estimate has a narrow confidence interval.

Moderate

We consider that the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. There are only a few studies and some have limitations but not major flaws, there are some variations between studies, or the confidence interval of the summary estimate is wide.

Low

When the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. The studies have major flaws, there is important variations between studies, of the confidence interval of the summary estimate is very wide.

Justification

Strong quality of evidence for recommendations based on primary literature and systematic literature reviews.

Related Information

Reference List

Relevant Resources

RESOURCE AUTHOR(S)

DISCLAIMER

The purpose of this document is to provide health care professionals with key facts and recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of patients in the emergency department. This summary was produced by Emergency Care BC (formerly the BC Emergency Medicine Network) and uses the best available knowledge at the time of publication. However, healthcare professionals should continue to use their own judgment and take into consideration context, resources and other relevant factors. Emergency Care BC is not liable for any damages, claims, liabilities, costs or obligations arising from the use of this document including loss or damages arising from any claims made by a third party. Emergency Care BC also assumes no responsibility or liability for changes made to this document without its consent.

Last Updated Apr 29, 2021

Visit our website at https://emergencycarebc.ca

COMMENTS (0)

Add public comment…

POST COMMENT

We welcome your contribution! If you are a member, log in here. If not, you can still submit a comment but we just need some information.